Goal Cascading

Effective goal setting is fundamental to the strength of any organization’s command and control structure. It is also one of the most important ways to improve employee retention and productivity. As goals cascade down from the top of an organization, they ultimately impact everyone within the organization. In the process, goals are transformed from being impersonal to personal. Through the deployment of Talent Chaser’s Task Action Planning (PATAP) Module, it has become clear that many managers fail to handle this transformation properly and that, as a result, employees can become demotivated and the organization’s command and control structure can be weakened.

In recent times, goal cascading has become a high priority process for many organizations. As a result, there are now a variety of online systems designed specifically for this purpose. Experience with such systems has revealed that, while they can work quite well where hard targets (ones that can be easily defined and measured) are involved, they are much less effective when it comes to the cascading of softer, more abstract targets. It turns out however, that, by integrating goal cascading into regular one-on-one performance appraisal sessions, this problem can be overcome.

Quantitative v Qualitative

A goal is quantitative if it can be stated in numerical terms. For example, a production volume goal requiring the production of a certain number of items/day is quantitative because the goal can be numerically stated. Goals that cannot be quantified in this manner are qualitative. All organizations typically have a combination of quantitative and qualitative goals and effective Goal Cascading requires that a clear distinction be made between the two. To be successful, it is necessary wherever possible to define goals in such a way that they can be quantified. With some types of goals, achieving this is relatively straightforward whereas others can require a degree of ingenuity. For example, quality-control goals appear, at first sight, to be qualitative in nature – how does one put numbers to quality? However, by defining quality control goals in terms of customer satisfaction survey percentages, for example, it is possible to turn them into goals that are quantitative.

By evaluating performance ratings garnered through the deployment of the PATAP Module, we have been able to ascertain that talented employees perform better and are more likely to remain as long-term employees when the organization within which they work, places high priority on the quantification of goals and where this is done in collaboration between managers and their direct reports.

Unfortunately however, not all goals can be quantified in this manner. Where, for example, the organization sets itself the overarching goal of being ethical in all of its dealings, it can prove difficult, if not impossible, to create some way of positing this as a quantitative goal. What might be perfectly ethical to one person might not be to another. While qualitative goals can be very useful, it turns out that placing too much emphasis on qualitative goals not only leads to a lack of accountability but also creates an environment in which misunderstandings and ambiguities can arise which adversely impact the goal cascading process and can result in increased employee turnover.

Through the deployment of the Talent Chaser PATAP Module, we have also learnt that for a goal to be quantifiable it must be possible to define it in such a way that it will be easy to reach general agreement on two related matters:

(1) Under what circumstances will it be clear that the goal has been reached?

(2) Exactly what series of quantitative tasks will need to be successfully completed for the goal to be reached?

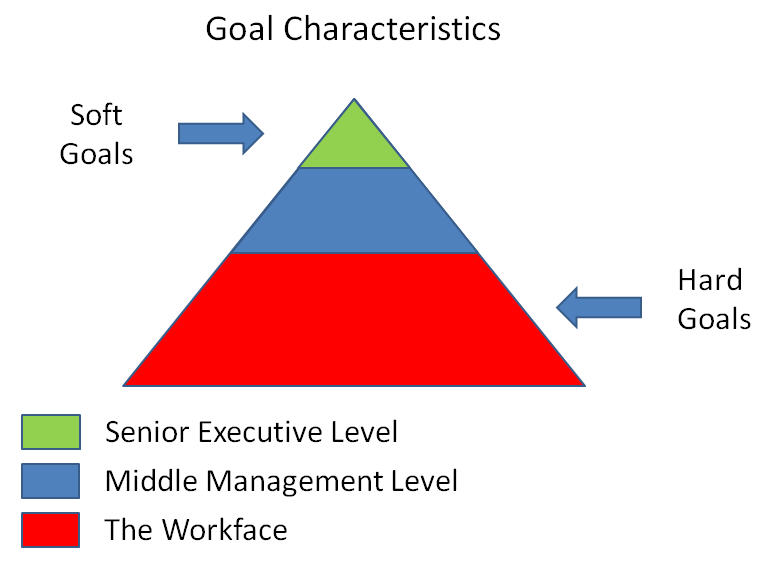

Where answers to both questions are available, the goal is quantifiable. In what follows, such goals are referred to as “Hard” goals. In the alternative, a goal is considered to be “Soft”.

Soft Goals to Hard Goals

In general, soft goals tend to be more predominant at the top of the organization because while it will usually be relatively easy to define the circumstances under which it will be clear that the goal has been reached, it will be difficult to set down the series of quantitative tasks that will need to be successfully completed at the senior executive level for the goal to be reached. For example, it would be relatively easy to quantify the series of tasks a welder, in an engineering organization, would need to complete in order to weld together the parts of an item being manufactured within a specified period of time. On the other hand, while the organization within which the welder works may have an overall goal of producing a specified number of such items per month and while the organization’s CEO would typically be responsible for ensuring that the organization meets all such goals, it would be much more difficult, if not impossible, to specify and quantify the series of tasks that the CEO should take in order to make sure this goal is reached.

As mentioned previously, as goals cascade they are transformed from being impersonal to being personal. But, this is not the only transformation that takes place.

As mentioned previously, as goals cascade they are transformed from being impersonal to being personal. But, this is not the only transformation that takes place.

As goals cascade down through the organization, they also have to be transformed from soft goals into hard ones.

Previously I described, using quality control as an example, how it is often possible to transform a soft goal into a hard one. However, cascading a soft impersonal goal (something that cannot be quantified) into a hard personal goal that can be quantified and used lower down in the organization turns out to be much more difficult.

It is this complex transformational process that traditional goal cascading systems often fail to handle very well. In practice, traditional goal cascading systems tend to work better at the lower levels where tasks and targets are typically more easily quantifiable.

It turns out however, that across a broad range of different types of organizations from for-profit to nonprofit, there are many instances where these are typically the very levels where information systems already exist for the management of workflow. For example, in virtually all manufacturing businesses, systems are already in place that set production levels and allocate output targets for each employee on the workshop floor (including, of course, the welder in my example above). Additionally, even within social services organizations, there are many areas where goals can be quantified. For example, it is usually quite easy to define the number of clients to be helped/served within a specified period.

What this reveals is that to a certain extent traditional standalone goal cascading systems to function best where they’re needed least. It turns out however, that when goal cascading is made part of regular performance appraisal and task action planning, the resulting interaction between managers and their direct reports promotes understanding and agreement. Command and control structures function best in organizations that ensure they have “buy in” when goals are being set.

You must be logged in to post a comment.